Writing a decryptor for Jaff ransomware

Overview

Recently, I’ve been trying to learn more about reverse engineering ransomware. Jaff is ransomware from a campaign dating back to 2017, and I was told that it had a vulnerability that would make it possible to write a decryptor. I analyzed a sample to see if I could rediscover the vulnerability myself.

You can find the sample I used on MalShare, and its SHA256 hash is 0746594fc3e49975d3d94bac8e80c0cdaa96d90ede3b271e6f372f55b20bac2f.

Initial Observations

The sample is a 32-bit PE excutable written in C++. The executable did not seem to import any functions related to cryptography, and it contained a very long chunk of encrypted data. This meant that the most important functions of this program were likely being decrypted dynamically.

By setting breakpoints on VirtualAlloc and VirtualProtect, I kept track of each time a RWX segment of memory was allocated. After several calls to VirtualAlloc and VirtualProtect, the program wrote a PE file to one of these segments, which I dumped from memory. This turned out to be the actual encryptor, and it’s what I’ll be focusing on for the remainder of my analysis.

Behaviors

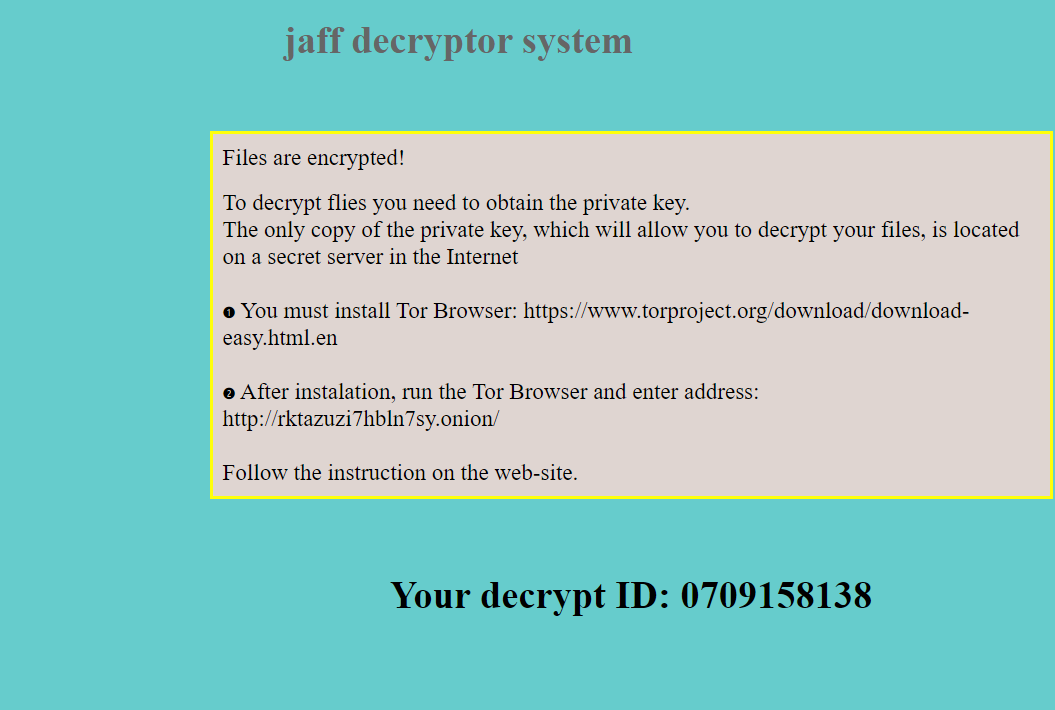

When run, the sample calls itself Ffv opg me liysj sfssezhz:

Additionally, a GET request is made to fkksjobnn43[.]org/a5/. As I don’t have access to this C2 server, I have no way of knowing what was expected from this server or whether the encryption process would have proceeded differently if I’d been able to connect.

Strings, Imports, and Resources

The binary I dumped from memory imports cryptography-related functions such as CryptEncrypt, CryptExportKey, and CryptGenKey, as well as file enumeration functions such as FindFirstFileW and FindNextFileW. This is how I knew I was looking at the actual encryptor.

Additionally, there were several resources containing data used in the encryption process:

-

#105: The string representation of the numbers35326054031861368139563306184134167018130718569482731666001650817539108744401016633231304437224730790638615766740272106403143256and35326054031861368139563306184134167018130718569482731666001650829864568371094444203557601170206844003631101722202233367975968667. #106: The file extensions to encrypt:.xlsx .acd .pdf .pfx .crt .der .cad .dwg .MPEG .rar .veg .zip .txt .jpg .doc .wbk .mdb .vcf .docx .ics .vsc .mdf .dsr .mdi .msg .xls .ppt .pps .obd .mpd .dot .xlt .pot .obt .htm .html .mix .pub .vsd .png .ico .rtf .odt .3dm .3ds .dxf .max .obj .7z .cbr .deb .gz .rpm .sitx .tar .tar.gz .zipx .aif .iff .m3u .m4a .mid .key .vib .stl .psd .ova .xmod .wda .prn .zpf .swm .xml .xlsm .par .tib .waw .001 .002 003. .004 .005 .006 .007 .008 .009 .010 .contact .dbx .jnt .mapimail .oab .ods .ppsm .pptm .prf .pst .wab .1cd .3g2 .7ZIP .accdb .aoi .asf .asp. aspx .asx .avi .bak .cer .cfg .class .config .css .csv .db .dds .fif .flv .idx .js .kwm .laccdb .idf .lit .mbx .md .mlb .mov .mp3 .mp4 .mpg .pages .php .pwm .rm .safe .sav .save .sql .srt .swf .thm .vob .wav .wma .wmv .xlsb .aac .ai .arw .c .cdr .cls .cpi .cpp .cs .db3 .docm .dotm .dotx .drw .dxb .eps .fla .flac .fxg .java .m .m4v .pcd .pct .pl .potm .potx .ppam .ppsx .ps .pspimage .r3d .rw2 .sldm .sldx .svg .tga .wps .xla .xlam .xlm .xltm .xltx .xlw .act .adp .al .bkp .blend .cdf .cdx .cgm .cr2 .dac .dbf .dcr .ddd .design .dtd .fdb .fff .fpx .h .iif .indd .jpeg .mos .nd .nsd .nsf .nsg .nsh .odc .odp .oil .pas .pat .pef .ptx .qbb .qbm .sas7bdat .say .st4 .st6 .stc .sxc .sxw .tlg .wad .xlk .aiff .bin .bmp .cmt .dat .dit .edb .flvv .gif .groups .hdd .hpp .log .m2ts .m4p .mkv .ndf .nvram .ogg .ost .pab .pdb .pif .qed .qcow .qcow2 .rvt .st7 .stm .vbox .vdi .vhd .vhdx .vmdk .vmsd .vmx .vmxf .3fr .3pr .ab4 .accde .accdt .ach .acr .adb .srw .st5 .st8 .std .sti .stw .stx .sxd .sxg .sxi .sxm .tex .wallet .wb2 .wpd .x11 .x3f .xis .ycbcra .qbw .qbx .qby .raf .rat .raw .rdb rwl .rwz .s3db .sd0 .sda .sdf .sqlite .sqlite3 .sqlitedb .sr .srf .oth .otp .ots .ott .p12 .p7b .p7c .pdd .pem .plus_muhd .plc .pptx .psafe3 .py .qba .qbr.myd .ndd .nef .nk .nop .nrw-

#109: The ransom note in HTML form, with the string[ID5]in place of the victim’s decryption ID. -

#110: The string.jaff, which is the extension appended to encrypted files. -

#111: The URLfkksjobnn43[.]org/a5/. -

#112: The ransom note in text form, again with[ID5]in place of the ID. #113: A string of bytes which, when XORed with the second number in#106, gives the stringsReadMe.txt,ReadMe.bmp, andReadMe.html.

Additionally, the string cmd /C del /Q /F %s found in the program suggests that it is intended to delete itself once encryption is complete.

The Encryption Process

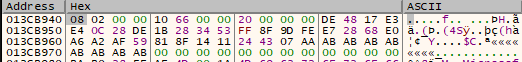

The sample uses 256-bit AES to encrypt files. For debugging purposes, I set a breakpoint on CryptImportKey to read the key blob from memory:

A new key is generated using CryptGenKey each time the program is run.

Beginning with the root directory, the program enumerates all files and subdirectories and uses CryptEncrypt to AES encrypt each file. The program uses GetLogicalDrives to find all drives connected to the system, and encrypts all drives that are not CD-ROM drives (possibly because a CD-ROM drive would make a noticeable noise as it started up).

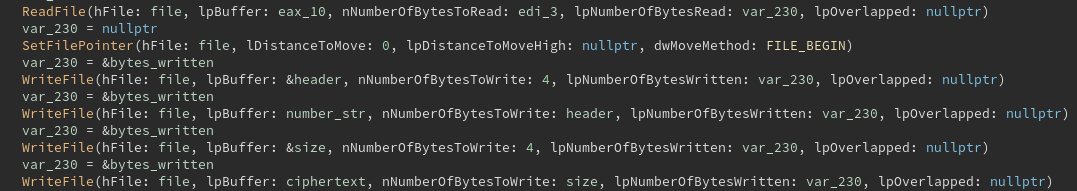

The .jaff extension is appended to the encrypted file, and the AES-encrypted bytes are written. We can see that there are multiple WriteFile calls to the encrypted file, revealing that something else is appended to the .jaff file before the encrypted data:

The appended value turned out to be the ASCII representation of a large number.

Additionally, the ransom note is dropped in each encrypted directory. The note is dropped in text, HTML, and image forms, with file names of ReadMe.txt, ReadMe.html, and ReadMe.bmp respectively.

A new victim ID is generated each time the program is run.

Encryption of the AES Key

I suspected that the long number appended before the encrypted data in the .jaff files was likely an encryption of the AES key. A new AES key was generated for each victim, so the program would need some way to store it.

Representing The Key Bytes

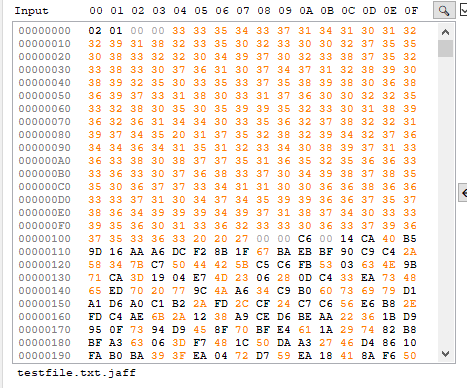

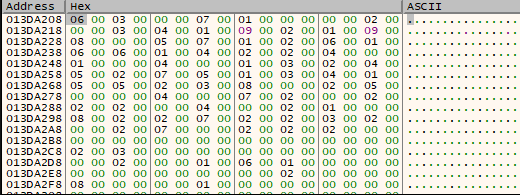

I found that the AES key was being passed as an argument to sub_402d70. When passed into this function, the AES key blob was being stored as a decimal representation in little-endian format, with each decimal digit being stored as a 16-bit integer. Each byte of the key blob was converted to three decimal digits; for instance, 08 would be stored as 008 and 8A would be stored as 138. Additionally, the digit “1” was appended to the sequence:

For example, during one run of the program, the original AES key blob was the following:

08 02 00 00 10 66 00 00 20 00 00 00 52 8A A4 D0 46 E3 4F FE E8 C6 A0 F5 91 0C 25 81 03 0E 5C 3C 57 F6 A0 43 08 32 C9 83 2C 01 FC 95

It was stored as the sequence of bytes

04 00 04 00 00 00 01 00 03 00 01 00 01 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 07 00 06 00 00 00 00 00 06 00 01 00 06 00 04 00 02 00 07 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 06 00 00 00 02 00 09 00 00 00 04 00 01 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 09 00 02 00 01 00 07 00 03 00 00 00 02 00 01 00 00 00 05 00 04 00 01 00 05 00 04 00 02 00 00 00 06 00 01 00 08 00 09 00 01 00 02 00 03 00 02 00 04 00 05 00 02 00 09 00 07 00 00 00 07 00 02 00 02 00 00 00 07 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 02 00 04 00 06 00 01 00 08 00 03 00 01 00 02 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 01 00 06 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 01

which corresponds to the number

1008002000000016102000000032000000000082138164208070227079254232198160245145012037129003014092060087246160067008050201131044

To convert this representation back into bytes, I used the following function:

def convert_from_decimal(s):

result = b''

s_fixed = s[1:]

for i in range(0, len(s_fixed) ,3):

curr_num = s_fixed[i:i+3]

result += int(curr_num).to_bytes(1, 'little')

return result

Encrypting The Key

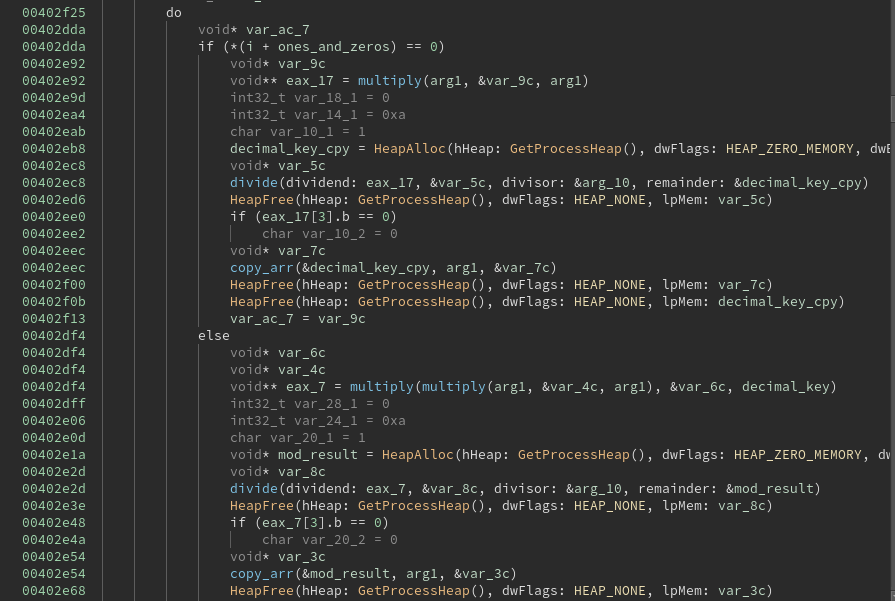

At this point, it was time to look at what sub_402d70 was actually doing. The arguments to the function were the AES key, an array of bytes that were either 1 or 0, and the decimal representation of the number 35326054031861368139563306184134167018130718569482731666001650829864568371094444203557601170206844003631101722202233367975968667. Note that this is one of the two numbers that appeared in resource #105.

By experimenting with this subrouting in a debugger, I found that the program was calling functions that performed multiplication and division on arbitrarily large numbers. Sepecifically, the AES key was being squared over and over, and something different was done with the result based on the values in the array of 1s and 0s.

This proved to be the repeated-squaring method for modular exponentiation. The AES key was being raised to an exponent, which was passed as an argument in binary form in order to aid in the repeated-squaring algorithm. The modulus was the long number stored in the resource.

The use of modular exponentiation immediately suggested that RSA was being used. Normally, this would mean we wouldn’t be able to decrypt the AES key, as we need the private key for that.

However, resource #105 contains two numbers, and we’ve only used one so far. One of them is the public modulus n, and the other number is very close to it. It seemed possible that the second number was phi(n), which is needed to compute the private exponent d from the public exponent e. I wrote the following script to test it:

def rsa_decrypt(msg, e, n, phi_n):

d = pow(e, -1, phi_n)

return pow(msg, d, n)

Sure enough, passing in the second number as phi(n) returned the decrypted AES key! Since the RSA key was hard-coded, this meant that we had enough information to write a decryptor for any files encrypted with this sample, even if the AES key changed each time.

The Public Exponent

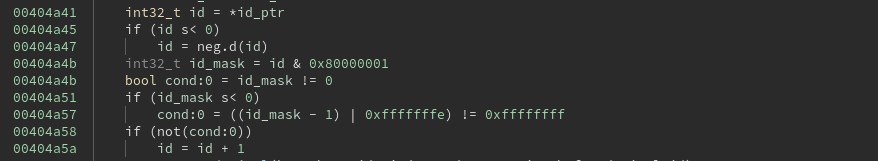

To generate the private exponent for the decryptor, I not only needed phi(n), but also the public exponent. However, the program generated a new public exponent each time it was run.

Upon closer inspection, I found that the public exponent was usually close to the victim ID given in the ransom note. Sometimes they matched exactly, but sometimes the exponent was slightly more than the ID, and occasionally they didn’t seem to match at all.

Eventually, I found that the victim ID seemed to be randomly generated. If a negative number was generated, the bits were negated in order to produce a positive result.

After correcting for this, I found that either the victim ID or its negation was always close to the exponent, but there didn’t seem to be much of a pattern to the exact difference.

It turned out that the victim ID sometimes needed to be modified before it could work as a public exponent. In RSA, the public exponent needs to be invertible modulo phi(n), meaning that the exponent and phi(n) need to be relatively prime. However, the process that generated the victim IDs did not guarantee a result that was relatvely prime to phi(n).

(This is just speculation, but my guess is that this is why phi(n) was hard-coded in the executable - they needed to guarantee that they had a valid public exponent, so they had to check whether the ID and phi(n) were relatively prime. However, this also gives us enough information to decrypt the files ourselves!)

By incrementing the victim ID until I got a number that was relatively prime to phi(n), I managed to retrieve the public exponent.

def get_relatively_prime(e, phi_n):

while(math.gcd(e, phi_n) != 1):

e += 2

return e

Putting It All Together

We now have enough information to write a decryptor that decrypts the victim’s files using only the encrypted .jaff file and the ID number in the ransom note.

import binascii

import math

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from struct import pack, unpack

phi_n = 35326054031861368139563306184134167018130718569482731666001650817539108744401016633231304437224730790638615766740272106403143256

n = 35326054031861368139563306184134167018130718569482731666001650829864568371094444203557601170206844003631101722202233367975968667

def convert_from_decimal(s):

result = b''

s_fixed = s[1:]

for i in range(0, len(s_fixed) ,3):

curr_num = s_fixed[i:i+3]

result += int(curr_num).to_bytes(1, 'little')

return result

def rsa_decrypt(msg, e, n, phi_n):

d = pow(e, -1, phi_n)

return pow(msg, d, n)

def get_relatively_prime(e, phi_n):

while(math.gcd(e, phi_n) != 1):

e += 2

return e

def aes_decrypt(ciphertext, blob):

iv = b'\x00'*16

key_bytes = blob[12:]

key = AES.new(key_bytes, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

padded_text = ciphertext + b'\x00'*(16 - len(ciphertext)%16)

return key.decrypt(padded_text)

def decrypt(filename, id):

#parse the encrypted AES key and data from the file

enc_file = open(filename, 'rb').read()

num_size = unpack('<I', enc_file[0:4])[0]

key_str = enc_file[4:num_size+4]

ciphertext = enc_file[num_size+8:]

keys = [int(i) for i in key_str.split()]

aes_key = []

#test both the victim ID and its negation for a valid public exponent

exp1 = get_relatively_prime(id | 1, phi_n)

for k in keys: aes_key.append(rsa_decrypt(k, exp1, n, phi_n))

if(str(aes_key[0]))[0:6] != '100800':

aes_key = []

not_id = ~id & 0xffffffff

exp2 = get_relatively_prime(not_id | 1, phi_n)

for k in keys: aes_key.append(rsa_decrypt(k, exp2, n, phi_n))

#decode the key blob from its decimal representation

aes_key_bytes = b''

for k in aes_key: aes_key_bytes += convert_from_decimal(str(k))

return aes_decrypt(ciphertext, aes_key_bytes)