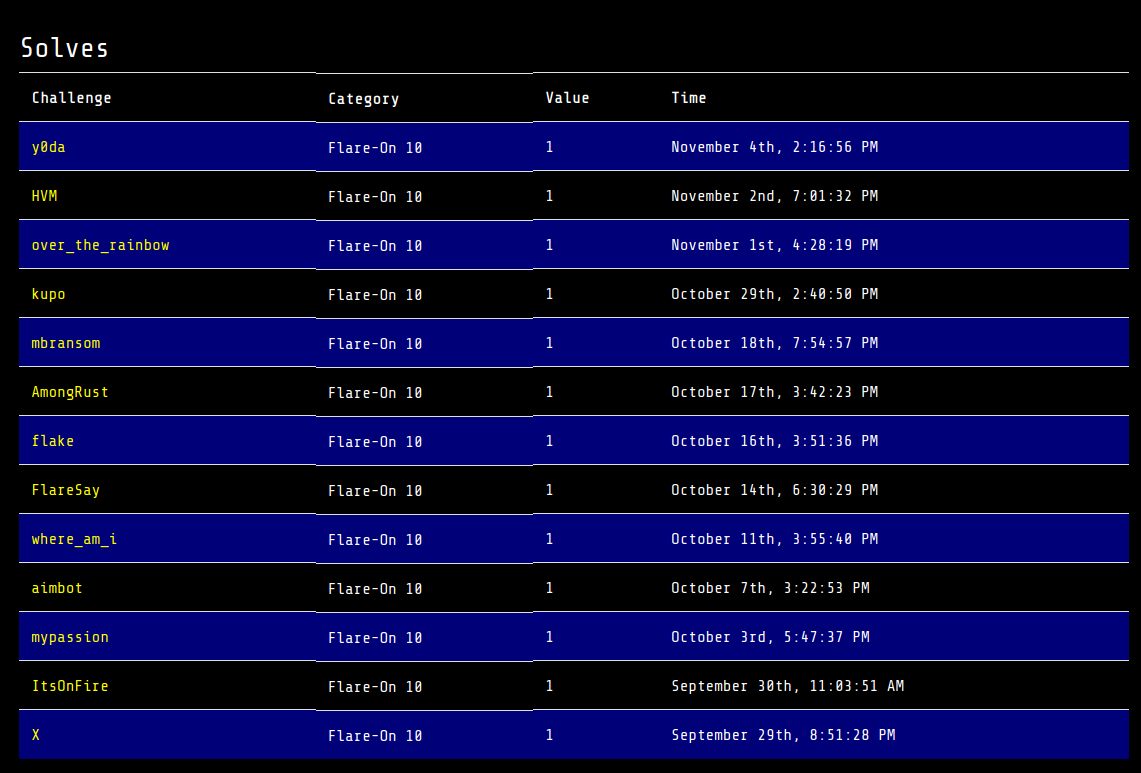

Flare-On 10 writeup: 11 - over_the_rainbow

This year, I completed Flare-On for the second time. Overall, I found the difficulty to be a significant step up from last year, and I finished with only a week left to spare.

I found challenge 11 to be one of the more interesting challenges, as it required a more in-depth understanding of cryptography than last year’s ransomware challenge.

Overview

We are given two files: the challenge binary FLAREON_2023.exe, as well as a file very_important_file.d3crypt_m3. This immediately tells us that we’re likely dealing with a ransomware sample, and that we’ll have to reverse the encryption algorithm in order to recover the file.

Running the binary without any arguments didn’t do anything, so the first step was to figure out the expected argument format. Looking through the strings, I found the string .3ncrypt_m3, suggesting that the program would only encrypt files with this extension. Presumably this is intended as a safeguard to ensure that people don’t accidentally encrypt their entire filesystem. After some experimenting, I found that the program took a directory as an argument, and it would then encrypt any .3ncrypt_m3 files in that directory.

After figuring out the argument format, the next thing I tried was to encrypt a test file. We can create a test file consisting of 0x1000 zero bytes with the command fsutil file createNew zeroes.3ncrypt_m3 0x1000.

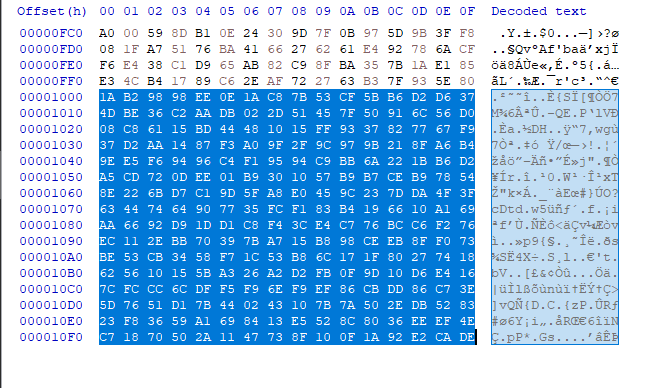

After encryption, the size of the file was 0x1100 bytes. This suggested to me that the original 0x1000 bytes of the file had been encrypted with a symmetric encryption algorithm, and that the symmetric key had been encrypted with RSA and appended to the end of the file. This is about what I was expecting, as most real ransomware performs its encryption this way.

The Encryption Algorithm

The Symmetric Encryption

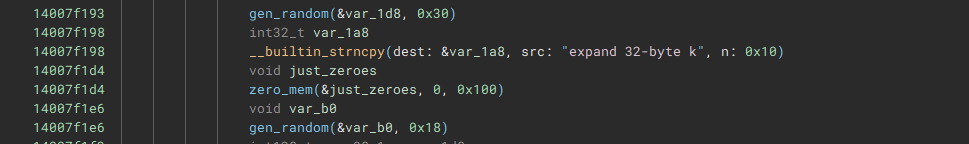

I noticed that the string expand 32-byte k appeared in the binary, which is a constant that is used in the Salsa20 and ChaCha20 encryption algorithms. This string is accessed in the function sub_14007ee60, and the string d3crypt_m3 is accessed in the same function. This indicated to me that sub_14007ee60 was the function where the actual encryption took place.

It looked like two different random keys were being generated. The first key was 0x30 bytes, and it was concatenated to the expand 32-byte k string to form the ChaCha20 matrix. The second key was 0x18 bytes, and it was XORed with the ciphertext after the ChaCha20 encryption was performed. Both keys were then concatenated together and RSA encrypted.

Looking at how the key was generated, I found that a new key was generated for each encrypted file. The function that generated the key bytes contained the string crypto\rand\rand_lib.c, which told me that OpenSSL’s random number generation was being used. This function uses BCryptGenRandom internally and it is cryptographically secure. This effectively rules out the possibility that we’ll be able to break the encryption by guessing the key, so to break the encryption we’ll need to focus on the RSA.

The RSA Encryption

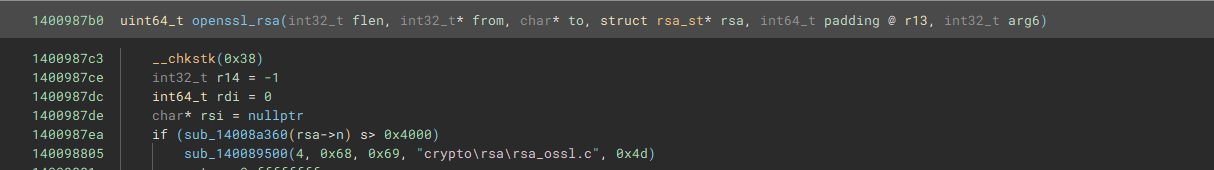

The RSA encryption function is located at sub_1400987b0. The strings in this function helpfully tell us that the source file is located at crypto/rsa/rsa_ossl.c.

Comparing this source file to the decompiled code, we can see that the encryption function is rsa_ossl_public_encrypt, and that its arguments and return value are given by static int rsa_ossl_public_encrypt(int flen, const unsigned char *from, unsigned char *to, RSA *rsa, int padding).

The struct RSA ia defined in crypto/rsa/rsa_local.h, and among other things it contains the value of the modulus N and the public exponent e. Setting a breakpoint at the RSA function in the debugger, we find

N = 0xc9c330728f68087afc60a133e49b9d3de49f0ff9995c5e12e5c65c11897bc718e3e4d272d5a58ce463755b2c63467f0d09f93c31cb67fe318809af7fc8b2c8c721ab547ce4db63dbdfff5d9b06c85799fdee690f90c479c6d0b9e3a3f66e55d63029ce5a02ef84c6aadc5e2241683024cc65d75642afe0babe76f29a677ceb159be48bb3265ebd2bd519a2af7e036cc2e6401c37555761a81c3d1d28a456c38b91b559035bff013dda0439053b9e96f4b278f719e939e677d058bc6e98005aff230814a497ab34b7fa902b666d180de84e24e90f753d79db0b7217acb5c46f4d1aa56bee573f2d47a4337ddd1e2b967edc7038feeb090dec7492d94d9689bb61

e = 3

We can also see that the padding argument is equal to 3, which corresponds to the constant RSA_NO_PADDING.

Breaking The RSA

For a modulus N, public exponent e, and message m, the ciphertext c is given by the equation c = m**e % N. The security of RSA relies on this equation being difficult to solve for m, but there’s one case where it’s easy: if m**e is less than N, we can find m by taking the eth root of c. If the public exponent used is large and if short messages are padded using a secure padding algorithm, this never happens, but this challenge uses a public exponent of 3 and uses no padding.

At 0x58 bytes, the message isn’t quite short enough to be recovered simply by taking the cube root of the ciphertext, but we can use a similar strategy. We know the last 0x10 bytes of the plaintext are expand 32-byte k. If we let m refer to just the unknown part of the message, tnd we let x refer to the known bytes expand 32-byte k, then the equation for the ciphertext is given by (2**16 * m + x)**3 = c. Expanding this equation out, we obtain a cubic which can be solved exactly for m, as shown in the following script using Sympy:

import sympy

from sympy.abc import m

N = 0xc9c330728f68087afc60a133e49b9d3de49f0ff9995c5e12e5c65c11897bc718e3e4d272d5a58ce463755b2c63467f0d09f93c31cb67fe318809af7fc8b2c8c721ab547ce4db63dbdfff5d9b06c85799fdee690f90c479c6d0b9e3a3f66e55d63029ce5a02ef84c6aadc5e2241683024cc65d75642afe0babe76f29a677ceb159be48bb3265ebd2bd519a2af7e036cc2e6401c37555761a81c3d1d28a456c38b91b559035bff013dda0439053b9e96f4b278f719e939e677d058bc6e98005aff230814a497ab34b7fa902b666d180de84e24e90f753d79db0b7217acb5c46f4d1aa56bee573f2d47a4337ddd1e2b967edc7038feeb090dec7492d94d9689bb61

c = 0x1336e28042804094b2bf03051257aaaaba7eba3e3dd6facff7e3abdd571e9d2e2d2c84f512c0143b27207a3eac0ef965a23f4f4864c7a1ceb913ce1803dba02feb1b56cd8ebe16656abab222e8edca8e9c0dda17c370fce72fe7f6909eed1e6b02e92ebf720ba6051fd7f669cf309ba5467c1fb5d7bb2b7aeca07f11a575746c1047ea35cc3ce246ac0861f0778880d18b71fb2a8d7a736a646cf99b3dcec362d413414beb9f01815db7f72f6e081aee91f191572a28b9576f6c532349f8235b6daf31b39b5add7ade0cfbd30f704eb83d983c215de3261f73565843539f6bb46c9457df16e807449f99f3dabdddd5764fd63d09bc9c4e6844ec3410dc821ab4

x = int.from_bytes(b'expand 32-byte k','big')

cubic = sympy.Eq((2**256 * m**3) + (3 * (2**128) * m**2 * x) + (3 * m * x**2) , ((c - x**3) * pow(2**128, -1, N))%N)

print(sympy.solve(cubic))

As expected, this gives us an integer solution: 0x06f7768ff2b963f356fc25b3443f7b729f68bcbdd65f22de685c3cb5c8a2697224368530e264fd388dc962f5d737cb873e24f39709d294224a5268c3512ddb6b3e54419b41c810cf.

The first 0x18 bytes of this integer correspond to the XOR key, and the remaining 0x30 are the unknown bytes of the ChaCha20 matrix. Since the XOR and ChaCha20 steps of the encryption are symmetric, we don’t have to reimplement them: we can just rename very_important_file.d3crypt_m3 to very_important_file.3ncrypt_m3, then set a breakpoint after the random bytes are generated and replace them with the ones we decrypted.

This gets us the flag: Wa5nt_th1s_Supp0s3d_t0_b3_4_r3vers1nG_ch4l1eng3@flare-on.com